| |

|

December

31, 2006

The old lords oppressed and humiliated

and injured for centuries. No one touched them. Now they’ve gone away.

They’ve gone to the towns, they’ve gone to foreign countries. Now

they’ve left these wretched people as their monument. This is what I meant

when I said that you have no idea of the extent which the victors won and the

losers lost here. V.S. Naipaul, Magic Seeds

Our tragedy on earth is that life is subject

to influences from above, and we can no more revisit the mistakes of

yesterday than the sand can avoid being wiped clean as the tide pours

upon it. Francois Bizot, The GateDecember 31, 2006. By bus from Saigon

to Phnom Penh, first through the Mekong Delta and then the western provinces

of Cambodia, another area that was heavily bombed by the U.S. I left

behind smooth pavements at the Vietnamese border and entered a bumpy

roadway lined with casinos under construction followed by two hours of

rice paddies and vast flat fields.

I have been reading Philip Short’s biography of Pol Pot and re-reading

Francois Bizot’s book, The Gate, about his capture and imprisonment by

the Khmer Rouge and the fall of Phnom Penh. Stayed in a guesthouse directly

across the street from the Tuol Sleng Museum, the site of S-21, the former

detention and torture prison run by the Khmer Rouge.

Pol Pot, who was first known as Sar, taught

French literature and was drawn to the poets, especially Rimbaud, Verlaine,

and de Vigny. He did not rely on notes, but spoke French with his eyes

half closed, concentrating on the words. He was gentle and considerate,

everyone said, a man of quiet charm and sophistication.

The detention center had been a high school, a common three-level masonry structure

that forms around three sides of a central playing field. Every floor had a

covered balcony that ran in front of the classrooms. There were three rooms

on the ground floor that had rusty beds without matresses where the interrogations

took place. Each room contained a large photograph on the wall showing the

dead body that had been left behind after the Khmer Rouge was driven from the

city by Vietnamese forces in 1979. In five or so rooms on the second floor,

several free-standing wooden blackboards contained photographs covered in glass.

These 4 x 5 shots of individual’s faces were arranged according to typologies,

such as women with the same haircut or men with caps. The photographs had good

tonal values and the photographer might have known Avedon’s work. They

were very aesthetic mug shots, if that is what they could be called, and it

made the vaunted heroism of documentary photography seem very odd.

My first responses were qualified by how

much this site of such authoritarian savagery looked like a lot of art

I had seen. The beds looked like Doris Salcedo, the blackboards like

Beuys, and the inventoried photographs of the victims like Richters’ Atlas.

The rooms of photographs—taken of young, very attractive, mostly

urban people who would be soon be subjected to unimaginable cruelty by,

mostly, rural young people—was compelling, but I did not know how

they were compelling. Can one respond to documentary photography after

becoming aware of its fundamentally fictive properties?

I came away thinking of Pol Pot and the

possibility that he once recited Rimbaud’s “Time of the Assassins” to

one of his classes.

I later read an essay by one of Pol Pot’s former students, the Cambodian-born

novelist Seth Polin, entitled The Diabolic Sweetness of Pol Pot. Polin, like

others who know the Khmer language and the precepts of Theravada Buddhism,

make much of how Pol Pot turned Buddhist principles into Khmer Rouge guidelines

and how he was able to use the power of language “to tangle sweetness

and cruelty together.” Sar was inspired by the “glamour of murder,” and

the national anthem is filled with imagery of blood, and a monastic stress

on discipline. Polin writes that Sar loved Alfred de Vigny’s poem “The

Death of the Wolf” and admired how the wolf dies. Referment ses grands

yeux, muert sans jeter un cri [In closing his great eyes, he dies without uttering

a sound]. “He admired the courage needed for that kind of death, the

courage of dying without crying out,” Polin writes.

And at S-21, the rule was: “When

getting lashes or electrification you must not cry out at all.”December

22, 2006. Visit to the studio of Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba. He works in a

well-restored 19th century French cottage. Well-lit domestic interiors

are unusual in Vietnam. His place seemed both antique and spotlessly,

cinematically, 21st century. I had not met him before, but I had seen

some of his films at Lehmann-Maupin in New York and looked at them again

in the SOC offices. In his Memorial Project Nha Trang, Vietnam: Toward

the Complex-For the Courageous, the Curious, and the Cowards (2001),

Nguyen-Hatsushiba filmed cyclos, the traditional Southeast Asian rickshaw/bicycle

taxis, being raced by young men across the ocean floor. I took this and

his other underwater films as extended metaphor for restrictive life

in Vietnam.

I thought he was an interesting guy, very soft-spoken and careful, but open.

When he was in grad school in Baltimore, Archie Rand would come down once a

month. He told me that Archie tore his work apart one day and it really started

from there. He asked me to thank Archie for him back in New York. Once again,

I thought about how in order to live here as an artist one has to want, and

maybe need, a limited amount of information; though in some ways that is naïve

on my part, as it assumes I am getting some kind of superior truth in New York.

Jun called Vietnam “a flexible place, more than some other developed

countries.” He said that the Vietnamese “will find a way to do

things, attempting something different is a challenge… I am here so I

don’t lose a kind of rawness.”

We looked at a lot of images of his work,

including a piece done in Laos, where a number of students from a local

arts and crafts school stood up in boats heading downstream on the Mekong

with easels and canvases. It was about how fast things are changing in

relation to traditions. Another work in progress depicts a field of water

bottles, all Coke or Pepsi products, through which figures move as if

working in a rice field, replacing the water with urine. A star formation

eventually forms. All of the work, the underwater films and the installations

and events, he said, he saw as monuments.

Vendler once wrote that the poets A.

R. Ammons, John Ashbery and James Merrill embraced "the thankless cultural

task of defining how an adult American mind not committed to any single

ideological agenda might exist in a self-respecting and veracious way

in the later 20th century."

December

20, 2006

I went to Dinh Q. Le's house in District 8, which is

a good way. Passed over a funky canal and some vintage warehouses,

French colonial and Chinese, and other varieties, the kinds of places

that Fowler

poked around in The Quiet American. A long way farther to a

relatively new area divided into lots and built with working class

dwellings. There

were plenty of open spaces around many of the houses, like Staten Island

forty years ago, farmland just recently opened to housing. No trees,

mostly brown, sandy dirt, made dusty from the wind. It must be brutal

in the hot

weather. All the assistance my driver solicited in order to find the

house helped humanize the area and made it peaceful.

Dinh's house is a great five-story structure he had only built a few

years previous. He has a collection of pots in the kitchen, including

an early Han pitcher with

those big old drips on it. His cook made us lunch as he took me on a tour

of the house. The breeze blew through it as we went up the stairs.

I looked at his

antiquities and French modernist colonial furniture, great stuff. I heard

later how he had wanted to return since he left by boat when he was

ten. He remembered

just walking out into the water one day with his family and there was a boat

waiting. When he saw this later it inspired the film he made for a project

in Singapore on Asian Diasporas. I had had dinner with a friend the

night before

and found out that she had left by boat with her family as well. Someone

else at the dinner the previous night mentioned how when he was a child

in Hue they

would lay dead Vietcong out on the road for a day or two as a warning not

to join. He used to walk by them on the way to school.

The afternoon with Dinh was an unexpected delight; he always seemed a little

distant around SOC, but was very warm when I was there as his guest. He gave

me a ride back into town on his motorbike and I mentioned I wanted to have

some shirts made. The next day he took me to his tailor and then to a market

to pick

out fabric.

December 16. I was given a house to stay in upon my return to

Saigon. It was in the ex-pat section, very close to downtown. I threaded

through

an alley created by rows of six storey buildings. A padlocked gate covered

the

entire

ground floor faćade, and then after that were another padlock and a keyed lock.

There was not much light on the lower floors. I walked into an entrance room

that was dark at midday. I set myself up in the large second floor bedroom with

antique furniture and wooden Buddha figures and began to work. I couldn't get

the DSL to start and then the pounding started next door. It sounded like workmen

were breaking through masonry floors with sledgehammers. This went on sporadically

for a while, various pounding and building noises, some shaking the building

a bit. I went to get something from my luggage and a bottle of talcum had opened

up in the bag. I thought, "Oh, I see, I am having a bad day."

For the next two hours I took taxis back and forth between my old hotel and

the house. By the end of the day, I was set up in my familiar hotel room

again and

given an office in a friend's apartment. Now, I look out of the sixth floor

onto the Saigon River. All the boats head leftward in the morning and the

other way

by the end of the day. This may be up and down stream. The building is an

example of French Colonial modern, probably from the fifties, with an elevator

that has

not worked in a long time. There are offices on the lower floors; at one

time they were all shipping companies, and the building is painted an aqua

blue that

must represent the sea. It's the same color I chose for my bedroom when I

was 11. Dark blue silhouettes of men and women emblazon the frosted glass

doors of

the lavatories that I pass when I climb the stairs. On the upper floors are

the plants and clotheslines that characterize most of the Vietnamese apartments.

There is plenty of Christmas around downtown Ho Chi Minh City and I can't

get away from it. I walked out of two restaurants at lunch so I didn't

have to

listen to rock and soul Christmas carols. Further downtown they were

blasting more Christmas "rock" that

sounded like Sting. The horror, the horror. I sat near the square formed

by the Opera House and the Hotel Continental the other night. This place

was once

the

center of Saigon, where everything happened. You could watch it all from

the veranda of the Continental, which is now a bland government-run hotel

of no

interest. The intersection is a wide, bald expanse of unremarkable macadam

and no one gathers

there. I had an ice cream down the street, where Duong, in The Quiet American,

got her milkshakes in the afternoon. There were large Christmas decorations

on the department store that went up near the Catholic school, on the opposite

side

of the square. I felt the artificial bleakness that comes with voluntary

solitude; it hurt a bit but passed in a matter of moments.

December 15. The day before I left Hanoi I took my bicycle to

the U.S. Consulate. I had to talk to someone in Consular Services about

my

passport, which had been reproduced on an announcement card and distributed

around

the

city. The

bicycle ride took me into the middle of early morning rush hour. I found myself

on streets that were solidly blocked up with people on motorbikes going to work.

There were also some bicycles, a car or two and a bus. It was like being in a

crowd—it was a crowd—but motorized; everyone had wheels and internal

combustion engines under them. The Hanoi air was terrible as I muddled

through. Everyone

was polite, though it seemed like misery to me.

Reading the Sunday Times Book Review online, I was taken with

the profile of Helen Vendler, both for the "loneliness" outlined in her

position outside theory and for her observation that she is unable to

completely

discern the

quality in the work of younger poets because she doesn't know the references.

She said

she never watched the cartoons that they did, which is a put-down, but

I knew what she meant. I mostly write about artists my age or older,

except more recently,

when an entirely new generation seems interested in painterly painting,

something I do not have to make a conceptual leap to understand.

When I visited Hans Josephsohn in Zurich he said something like, "There is only

so much that you can do with sculpture." I admitted to myself that I

do believe there is only so much that you can do with painting, before

you're

throwing

a red herring out to distract the viewer from the fact that you're not

interested in taking on the problems of painting. But the painters who

have actually taken

those problems dead-on continue to surprise. Warhol turns out to be an

astounding painter. I sometimes think of a character of Iris Murdoch's

in The Book and

the Brotherhood, who had plenty of money but always served second rung

wine and collected prints by secondary artists. He thought it was vulgar

and unrealistic

to have only the best around him, when what he did surround himself with

was suitable.

I think painting is an unsuitable vehicle for outsized ambition at the present

time. The news from abroad on the Currin show makes me think this, but if

you put some abject dot on the canvas, it's just as ambitious. It's one of

the few

mediums with the ability to reveal itself over time, but no one has the patience

to let it do that. It's no better over here than in New York.

|

|

|

|

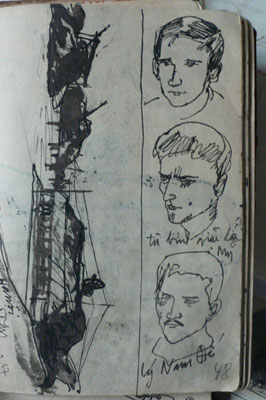

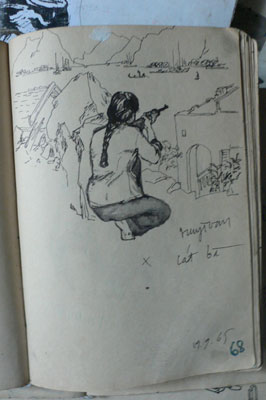

December 12. I had asked Tran Luong to arrange for me to visit Huy Toan, who was included in the Saigon Open City Exhibition. He had been in both wars, the French and the American (and even the Chinese invasion in '79). We went to his house and it was dark in the afternoon, the entire sector had a power outage, so we looked at his work by the open balcony. He had several dozen notebooks filled with sketches from the years of the wars. There was a dummy of a monograph that was being published, pasted with drawings from photocopies of the originals as well as many originals; one was of the mountain road that led to Dien Bien Phu where all the military equipment had to pass.

December 12. I had asked Tran Luong to arrange for me to visit Huy Toan, who was included in the Saigon Open City Exhibition. He had been in both wars, the French and the American (and even the Chinese invasion in '79). We went to his house and it was dark in the afternoon, the entire sector had a power outage, so we looked at his work by the open balcony. He had several dozen notebooks filled with sketches from the years of the wars. There was a dummy of a monograph that was being published, pasted with drawings from photocopies of the originals as well as many originals; one was of the mountain road that led to Dien Bien Phu where all the military equipment had to pass.

Huy Toan would draw everything during the invasion of Danang. He followed the troops in, and as they marched by, he saw a man and woman coupling in a field, oblivious to what was going on around them, so he stopped and drew them. Some of the sketches shocked me. There were a number of portrait sketches of American pilots. He said that he got to know them in Hanoi, that they were held in different places around the city.

He could go wherever he wanted and draw because he was a colonel in the Ministry of Information, and he was an important figure in the propaganda department: his drawings were used in many posters and comic books. He was admired by the younger Vietnamese artists, like Tran Luong, who knew his comics from when they were children. They all recognized that his comic books were of greater artistic quality than most. There was in particular in the cabinet at SOC about the Christmas bombings of '73, with images of Nixon and of John McCain standing in a lake in Hanoi.

The house was full of his oil paintings and gouaches; almost all of them had a war theme of some sort. It appeared he was continuing to work from the material he collected in his notebooks. I looked through at least five of them; they documented military life, battles, artillery, women (in combat, entertaining the troops, and at more casual moments), and sites that had been leveled in bombings ("That's a hospital, that's a school..."), as well as battlefields, cityscapes, portraits, sketches of weapons and common objects, men in groups, architecture in landscapes ("That was bombed after I moved out").

I asked if he was interested in any other artists. He gave Tran Luong, who was translating for me, a very, very long answer.  He said that he was born in 1930 and, when still very young, there was the Japanese-Mussolini-Hitler alliance. The Japanese occupied Vietnam, then it was given back to the French, and there was the famine. He saw "terrible times" and felt that the Ecole des Beaux Arts had "romantic attachments" and was disconnected from life. He was more drawn to the realism of French comics. Tran Luong said later that he was considered to be unique, a self-taught artist, and that he was not close to any of the fine artists but still kept up with other war artists. He was a very friendly man. He said that he was born in 1930 and, when still very young, there was the Japanese-Mussolini-Hitler alliance. The Japanese occupied Vietnam, then it was given back to the French, and there was the famine. He saw "terrible times" and felt that the Ecole des Beaux Arts had "romantic attachments" and was disconnected from life. He was more drawn to the realism of French comics. Tran Luong said later that he was considered to be unique, a self-taught artist, and that he was not close to any of the fine artists but still kept up with other war artists. He was a very friendly man.

For what China proves (though this is left unsaid) is that an authoritarian system helps rather than hinders economic growth on the neo-liberal model, by ensuring that labour laws, trade unions, the legislature, the judiciary and the fear of environmental destruction do not impede the privatisation of state assets, the appropriation of agricultural land, the provision of subsidies and tax cuts to businessmen, or the concentration of wealth in fewer hands. —Pankaj Mishra

Ascetic ideals constitute today a more solid bulwark against the madness of the profit-economy than did the hedonistic life sixty years ago against liberal repression. —Theodor Adorno

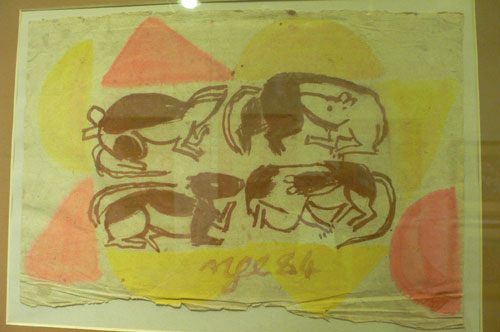

December 9. I met a self-described art-lover at an opening last night, and this morning I went down to Ryllega gallery to let him into my exhibition. I take it down on Tuesday; that is why I'm back here.  As I lifted the gate and entered the space there was that musty masonry and moisture smell from Paris stairways. Oh, and it was a Saturday here like the ones I have in Paris in late November, with an extra dollop of melancholy, for some reason. The whole afternoon was Parisian, taking my bike around and witnessing the small shocks of decaying beauty on the side streets, sitting outside in the chill and overcast to eat Vietnamese steak frites at a Bia Hoy where several avenues converge on an open square. The pushy, slightly feminine arrogance of the jacketed young men horsing around in front of the restaurant. After lunch I went back to Mai gallery and spent time with Nguyen Tu Nghiem's gouaches. I wish I could afford to buy one. They had a watercolor of mice surrounded by geometric shapeson a wrinkled piece of rice paper and another of two Vietnamese musicians so heavily painted that it the image was layered in crumbly flakes. Later, I had a mille-feuille and an espresso, went to the Musee De Beaux-arts to look at the old porcelains and then went to the Hanoi Cinemateque. As I lifted the gate and entered the space there was that musty masonry and moisture smell from Paris stairways. Oh, and it was a Saturday here like the ones I have in Paris in late November, with an extra dollop of melancholy, for some reason. The whole afternoon was Parisian, taking my bike around and witnessing the small shocks of decaying beauty on the side streets, sitting outside in the chill and overcast to eat Vietnamese steak frites at a Bia Hoy where several avenues converge on an open square. The pushy, slightly feminine arrogance of the jacketed young men horsing around in front of the restaurant. After lunch I went back to Mai gallery and spent time with Nguyen Tu Nghiem's gouaches. I wish I could afford to buy one. They had a watercolor of mice surrounded by geometric shapeson a wrinkled piece of rice paper and another of two Vietnamese musicians so heavily painted that it the image was layered in crumbly flakes. Later, I had a mille-feuille and an espresso, went to the Musee De Beaux-arts to look at the old porcelains and then went to the Hanoi Cinemateque.

December 8. Landed in Hanoi. Damp & overcast. The previous night in Saigon I went out to Tran Trung Tin's house with SOC assistant curator Quynh Anh Tran. I had asked her to come along to help me translate a few weeks ago, and by the time we had gotten there, after a few cancellations on my part and more interactions with her around the SOC offices and dinners, I found that she was charming, very young and very smart. Mrs. Nga, Tin's wife, had allowed me to visit after I went to her gallery and gave her the link to the Artcritical.com piece. There were a number of Tin's early Hanoi works framed and on the floor downstairs; Quynh Anh noticed that the framing left the works vulnerable to changes in the weather, and a number of these beautiful paintings seemed damaged by mold or moisture. A portfolio that Mrs. Nga then brought out had a good many figurative works from the same period. There were a number of themes that I recognized from his monograph, such as the young girls shouldering rifles. There were some paintings on newspaper of figures gathered under a vertical structure of some sort. These works depicted figures that would gather under streetlights at night. With the power shortages during the war, these public spots were dating magnets, like drive-ins, for Hanoi teenagers. We went upstairs and met Tin, who was very friendly and smiling. He had short hair like mine, which he commented on right away, and he was still good looking, almost like an old sculpture of the Buddha, with his long ears.

December 7. There is no difference between my writing and my painting that I am aware of. I only have one form of address, and that is to one person at a time, with me not present. I use the materials at hand, found in the studio or bought beforehand, and try and put them together in such a way that it doesn't tire them. The experiences are givens, too, and have to be set down fairly fresh and left alone as much as possible, but the prose is combed often. This is the advantage of the diary form; it lets the material shape itself. There is an internal structure to be attended to but not an overall architecture. This is just as true with critical writing, but the architecture is present. It still has to be done in such a way that the material doesn't go stale, so you have to write to find out what you think, not write what you already think. All of these ways of working are about intimacy. Rereading The Quiet American last week, I was conscious of observations that came from the character observing himself. My favorite line is: "That loosening of the bowels one feels when one is about to have a new experience," or something like that. Greene indicates that the book was written over three and one half years, so he must have been moving very slowly through what he was thinking and experiencing. He probably wrote it to find out what he was doing there (here).

December 5. Back on the tropical island again. Floating in undulating saline solution under the hot sun. I could barely get out of the ocean all day. And I could not bring myself to leave the beach until the sun dropped under the horizon. A pink ball on a dirty blanket. Not a hint of drama in that sunset. Perfect. Trollope's Barchester Towers, a beach book for the ages.

For the Saigon Open City (SOC) experience in full, you will have to wait for the Art in America article, so many notes, so may things to digest. I spent most of the past week in SOC's offices as a kind of ghost editor; I rewrote everyone's copy, all the introductions and the brief bios of the artists. I was useful as someone who had better English grammar, but I had no faith in this because I only knew what I knew by ear. I am considered to be the most fluent English speaker as well as a writer. And the curators were all Vietnamese, Thai and Danish. I kind of love them. Also, I had yet more evidence that Tran Luong is a saint. And another Vietnamese, Dang Giang, the Director of Communications, was quietly fascinating. He reminded me a little of the Edward James Olmos character in Miami Vice. I had not met him or heard of him before. He seemed more open to casual, intimate conversations, too. He had left Hanoi for then-East Germany is 1984 and before the breakup of the Soviet bloc, he slipped out and landed in a refugee camp in Austria for six months. It was pretty boring, he said. "You get three meals a day, but there is nothing to do, nothing even to read. I was lucky, some people stay there for years." He has a website where political issues can be freely discussed, but it is illegal in Vietnam. People can read it but cannot add their own comments.

I was an outsider. I was supposed to write about them, and in a sense there was no journalistic distance. It was a way of becoming familiar with all the material that I would have had to read anyway. I don't know the last time I was in a collaborative situation. Probably the 80s when I did some set work for an experimental theatre company. The hardest thing was to keep my mouth shut and be a worker among workers. I knew there was no time to fool around or get to know anybody, to ask them questions about themselves, so I just became the guy that said, "More text, please." Whenever I went to the far room where all the older works from Vietnamese artists were being reframed, I got excited. When we went out for meals there was talk of what to do next, and I kept quiet there too because I had nothing to add. I asked some questions if they seemed to have the time.

Being that I am a painter and not as involved with art as social interaction as was the overall theme of the first part, I was at a little distance. But I felt hugely supportive of all the work going on, thrilled to be part of it, though I had reservations about some of it, too. Perhaps it was just the outsider feeling creeping in, and the fact that I would have liked to be choosing the older Vietnamese painters.

One day I transcribed the Martha Rosler film, Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained. All the films had to have their complete transcriptions translated into Vietnamese and submitted to the Ministry of Culture for approval. I put it on the computer and went through it, stopping every sentence or two. There was a voice-over as well as on-camera dialogue. Martha Rosler has a sense of humor as well as rage. And a Brooklyn accent. That she, the artist, was the subject who was stripped and measured the film was admirable. Similar to a director who plays the part of the most unlikable character in their film, Rosler took the "I wouldn't ask anyone else to do this" part.

"I noticed how her eyes followed him to the door and as I passed the mirror I saw myself: the top button of my trousers undone, the beginning of a paunch." -- The Quiet American.

return to blog index

|

|