|

|

November 30. Yesterday the Fulbright Enrichment Seminar began. I was in a van full of scholars and students heading out to The University of Dong Thap, a remote province in the Mekong Delta. I was dreading it. I avoid overland trips as much as I can and miss a lot because of it. Driving under the hot sun, crawling through greater Ho Chi Minh City, which goes on forever, was particularly tough. I tried remembering that every situation and feeling passes. It took five hours to get here. I had a headache that didn't leave for 24 hours. Last night, a few of us took a walk, and as we sat around drinking cane sugar juice or orange juice, I blurted out that I am an optimistic person and that this was going to be dreadful.

Soon, this feeling passed. I have been eating baguettes with butter and jam for weeks and looked like a pig in the mirror, so I ordered fruit and yogurt. All the other Fulbright people with me speak Vietnamese, and I was the first at breakfast in the large dining hall. There were a few people at the other tables. The staff, country people circulated, working in a hotel where only occasional foreigners come through. There was no menu and I had a hard time even ordering coffee. I don't know if it's the language barrier or the my foreignness that kept the woman from understanding. If I could just once remember my Viet glossary.

A larger hall on the other side had set tables with hot pink bowls and cups. Another table had the same thing in a parrot green color. They were already blasting some kind of pop music over there for a wedding reception later on. This is typical of Vietnam and I am getting used to it, used to the odd smells in the drains and sulfurous tap water, the variety of large potted plants everywhere—lines of them on cement in the parks. This hotel was spread over several acres, more like a compound behind a wall, and had a number of decorative artificial ponds and lines of plants in large round planters.

After the day spent at the seminar, there was enough time to head over to the public pool, about a ten-minute walk away. I knew from past experience that it closes at 6pm, so at 5:10 I grabbed a motorbike taxi. There was one sitting at the front gate of the hotel, and he took me over for 5,000 dong, about 30 cents. It was a large modern sports building surrounded by a decorative iron fence and the next building over was also large and modern-ish, with some rounded windows made from cast concrete. There was a pictograph of a figure swimming above the Vietnamese writing on one side and the Olympic insignia on the other. A tall friendly man, taller than me—that's tall for a Vietnamese—with a little potbelly, came out of an office and I made some swimming motions. He directed me outside to where there was a woman in a concrete booth with her baby in a basket. I handed her 10,000 dong and she gave me 5,000 back, along with a bright red ticket. I returned inside, handing it to the man. This is also typical of how things are done here.

The man then led me past some smudged rooms with lines of broken doors and up a flight of tile stairs. There was a depression in the landing where there once may have been water for rinsing feet. Everything was soiled and worn, not terribly so, just not kept up. The top of the stairs opened up onto a huge deck with an Olympic-sized pool under a big sky. It was flanked by grandstands that could each hold a few hundred people. The lanes in the pool were divided with big plastic chains and there were numbered perches. There was no one there. Off in the distance there was a smaller pool with a few boys playing in it. I gesticulated as to where I might change, and he pointed off to a changing room. The changing room also looked as if it is never used. Dead flies covered the windowsills and the floor was scattered with them.

But the pool itself looked well-scrubbed. I jumped in and begin to breaststroke. The water felt fresh and there was the bite of chlorine in my eyes. Three of the pool's employees came up to watch me so I worked at my laps a little harder than I might if I didn't have an audience. I tried again to re-teach myself the crawl and that tired me even faster, so I went back to the breaststroke. At one point after twenty minutes, one of them shouted "Finished?" I raised my finger for one more lap. When I got out he came over and tried to converse, but it was no use. I pointed my finger at the pool and raised my thumb to indicate No.1 (Great). He smiled and a few minutes later, dumped a bucket of chemicals into the pool.

I walked downstairs and there was beautiful music playing in the office. It sounded a little like Gamelan, but there was a kind of nasal whine in it that sounded traditionally Vietnamese, a woman was singing in the foreground. I walked out of the building and a woman setting up her food stand on the wide sidewalk in front of the building had the same music playing from a speaker somewhere. I stood there as dusk fell and the smell of smoke began to rise and listened to the music for a few minutes. The woman looked at me as if maybe I wanted something, but all I could do was point to where I thought the music was coming from and raise my thumb. The distortions that muffled the edges of the singing seemed to nestle it into the evening.

Around the buildings, food stands were being set up and there were collections of rusty beach chairs to recline in. This was a country town, so all the kids said hello and many of the adults too, as they watched the curiosities walk by. I was reminded again why I come here, heading back and peaking into the little improvised hovels and huts. I passed a Buddhist temple where two men on the steps beckoned me to come in. The sun went down, the few lights came on and the smoke in the air was stronger.

In The Quiet American, Fowler admonishes Pyle for wanting to help the Vietnamese. "Next you'll be calling them childlike." It's a tale of Western projection. Vietnam as a young girl in need of protection. Fowler claims he is happy to exploit them, to exploit his young lover, Phuong, in order to ward off old age and loneliness. After a day spent with my Fulbright colleagues, it is more obvious to me than ever that I have a similar, tourist relationship to this country, not so much like Pyle, but a little like Fowler: Vietnam as a place to escape into. I am engaged and disengaged at the same time. One part of me is interested in the culture and the history, etc. and the other is using it as a springboard for something purely subjective. Graham Greene was very fond of his childhood adventure books.

As I walked down the road I thought about a time when I was a child. We spent part of the summer in the Adirondacks. It seemed like the only place where my father, a harsh, driven man, became human. Once there, he almost wasn't dangerous to be around. We would often go to the beach at one of the nearby lakes and stay until after dinner, the sun set very late there. He used to walk us through the campsites surrounding the lake after dark. Parked cars, different kinds of tents to peer into, woodsmoke and mosquito nets over the front, people cooking or reading. This was the late '50s and early '60s, before those places filled up with RV's. He held my sister's hand and my own and whispered to us as we walked past the campers and their semi-improvised architecture, how they sorted themselves out between the trees, the picnic table and the grill. Some campers quietly said hello to us as we went past on the macadam. It must have been a very welcome and rare moment in a very common, strained childhood. I found it again fifty years later. Maybe that is what keeps drawing me back, that I want to repeat that moment. But the thought didn't detract from the charm of the evening.

November 25. David Ross, former director of The Whitney Museum, opens Saigon Open City by giving a talk about the work of Yoko Ono. Her "War Is Over If You Want It, Love John & Yoko" banner is to be strung across the War Remnants Museum. Ross has curated her portion of the exhibition. He speaks of her and John Lennon's opposition to the war, and their "cynical and practical" decision to use their celebrity status to oppose the Vietnam war by creating Bed Peace (1969), in Montreal. John was having visa problems in the U.S.. He mentions how, unbeknownst to them, John and Yoko were on Nixon's "enemies list." Earlier, Ross had recounted how Yoko had gone through WWII hiding in the countryside and of her experience returning to Tokyo and finding it devastated. He showed some pictures by Richard Avedon of Vietnamese napalm victims that Avedon had chosen not to release when they were taken thirty years ago. There was a Yoko Ono flashlight peace, a gift to the people of Ho Chi Minh City, where one flashed Morse code for "I Love You," and another piece "I Love My Mommy," where a large blank canvas was supplied for people to draw pictures of their mother. Ross showed a portion of a film of John and Yoko. Then he played "Imagine" and invited everyone to sing along. A dog and pony act. But at one point, he said something I found interesting: "We are here because we love art, we love museums."

November 21. Bush had arrived in Saigon that evening and the taxi we took across town was diverted as one street after another was closed to traffic. Invited to a dinner at the house where the curators for Saigon Open City, the first international Exhibition in Vietnam since 1962, are staying. Mary already knew Rirkrit Tiravanija, whose reputation preceded him, from the Whitney Program. Along with Gridthiya Gaweewong, also from Thailand, they were the head curators. Also there were Cecilie Gravesen, an assistant curator, studying in London, from Denmark, and Quynh Anh Tran, another assistant curator, who was Vietnamese. We thought the invitation was offhand and we weren't sure if it was even on, and I had wanted to go to the Opera House, where there was a program with the Danish Symphony. There is not much of traditional high culture in Saigon, let alone films, or many books in English, and there is only a program at the Opera House twice a month, but I decided to go to the dinner.

We arrived late because of the traffic diversions. We were apparently the central figures at the dinner. They had waited for us and the table was set, the food was out, and no one had begun. This kind of consideration goes a long way with me, not that I like to be treated like a special person, but I like when the formalities are observed. Rirkrit had begun his art career by cooking Thai food for whomever came in the gallery for one of his first exhibitions. He made everything that night. It was a lovely assortment of very spicy Thai and Vietnamese food, fish, vegetables, Pad Thai (one of my favorite things), all done with a rich turmeric-colored peppery sauce.

Tran Luong had asked me to support SOC and I volunteered my services. I went over how I had exhibited in Saigon in '04 and how I had to go through the censors at the Ministry of Culture, how we had to translate all of the titles of my abstract paintings into Vietnamese so that they could understand and approve them before the show opened. The exhibition before mine at Mai's gallery had large portions of what was on display masked by the censors. They had covered very mild nudity, mostly pictures of women in bathing suits, or fragments of text in French that they claimed they did not understand. By allowing this censorship the exhibition got its license to open. Last month, Tran Luong had indicated to me that those days were over, but it was apparent that the Open City curators were having trouble.

Saigon Open City had an ambitious program with exhibitions in four museums, various individual talks by artists scheduled, and a number of exhibitions at the SOC site, in an old navy warehouse by the river that now had several offices and exhibition rooms. During the conversation, I mentioned the desire to control information. Rirkrit said that there was nothing so easy to describe; the situation was not any large form of control by the government, but rather a lot of individuals in not so important positions with the power to hold things up, which they exercised. In some cases wanted a bribe or some other form of compensation, like wanting to doing the construction work required for an exhibition at a particular museum. The curators weren't always willing to go the usual route and that seemed to cause some problems, too.

They were obviously committed and serious. They had been working on the exhibition for months and it was a two-year program in three parts. The project was conceived of in three chapters. The first chapter focuses on social reality as portrayed through the daily life of Vietnamese people during the Liberation period from 1946 to the present, through Vietnamese and concurrent international art. I emailed the Press Release to Artnet.com and had been checking every day to see if something about it had gone up on the site. E-Flux, another site had picked it up and distributed it.

I sat at the dinner and thought about how everyone there was younger than me. I had already been sizing Rirkrit up, and I was impressed with his intelligence and self-assuredness, a certain kind of quiet charisma, even, and maybe less impressed with what I thought was his detachment. But then that may be another way of looking at native self-confidence, something that I have certainly seen in plenty of artists. When I see it in people that I perceive have never been shaken from it, when their instincts have proven them correct, I always feel that I am staring at some slightly different species than my own.

November 20. Ho Chi Minh City is increasing in population rapidly, five times faster than Hanoi. Money is made here, and speculation on what might trickle down is such that the poor from the rural areas are flowing into the city to seek a better living. This has resulted in some new slums, just like in new global cities, like Mumbai. Theft is a big problem. I was recited a list of what had been stolen from one resident over eight years: two laptops, a number of cell phones, a Blackberry that was snatched off in motorbike traffic, two large amounts of money, televisions...

Slogging through a lot of hotels in the cheap area, called Pham Ngo Lao after the street of that name, I looked into my old place from two years ago. I had been there for three weeks while working on my show, and the old woman that ran the place, who used to smile and coo and rub my face whenever I came downstairs, didn't remember me. I already had a grandmother anyway. While Mary was looking into another place, a man beckoned me across the alley to his mini-hotel.

I'm still here. It's immaculately clean, there is beautiful light and it's very quiet. The owner is a doctor who works with the poor. His wife makes fresh yogurt, served with the airy baguette that is put out for breakfast every morning. I see the bread coming from ovens about a block away. As I run out the door, the doctor's wife touches my shirt to ask if I want it ironed. They moved out the extra bed in my room and brought in a desk and stool for my laptop.

I originally considered getting my own place in Saigon. I could return there after going off to Cambodia or the Mekong Delta. I received news of a large, airy apartment with a balcony and high ceilings. The previous tenant, "an Englishman," had vacated at the news that the building would be coming down. But the landlady had too many tenants than she could legally dislodge and now she was renting again. I met a Northern Irish ex-pat in Hoi An; he had been living in Saigon for years. He told me that those apartments were hard to come by these days.

I went to see the apartment up two flights of lightless, windowless stairs. A rusty gate was pushed back. It was light and airy, all right. Then I looked out the windows to the surrounding buildings and half the apartments were ravaged shells, with garbage on the roof below. My view would not change. As it happened I got an email that day from another Fulbright grantee that was in Saigon a year ago. He said: stay in a mini-hotel and they will watch your bags when you are away. Apartments get burglarized.

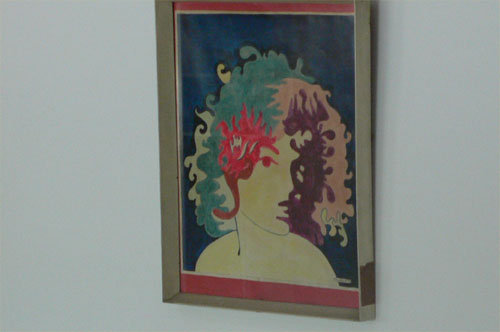

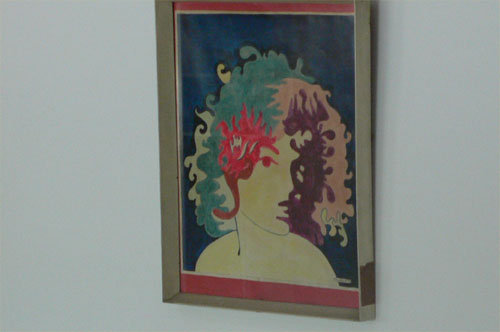

We went to the Reunification Palace, the renamed Presidential Palace of Diem and Thieu, South Vietnam's last presidents. This is one of my favorite places, which has much to do with Ngo Viet Thu, its Vietnamese architect who was trained in France. There is very little modern architecture of interest in Vietnam. His is a lovingly designed modernist building from the early 1960s. It was built on the site of an older colonial palace. The pretty fountain on the large lawn has mixed tiers of water jets. The building is surrounded with an assortment of tall trees and a park. The semi-ornate front gates, where the Russian tanks broke through during liberation, remained from the earlier palace. Inside are Vietnamese paintings and murals that were contemporary, including a very odd psychedelic portrait. It resides in the den-like recreation room, which contains a wrap-around polychrome leather couch and round, intimate bar that resembles a barrel. The lower floors, that contain the presidential receiving room, were closed for a private function. This was unfortunate, as there were also banners announcing the event across the fa¨ade.

I hadn't been in the basement before, where the war rooms are. The exhibition design heightened the desperation that must have been felt in these rooms. One passed through narrow, heavily repainted, military gray-green hallways to view the individual offices. Many of the small spaces, lit from above with fluorescent light, contained stacked units of communications equipment on three walls—vintage black boxes with toggle switches and dials—while other rooms only had a desk, a chair, a filing cabinet and two or three of telephones in different colors. It was a mystery. All of the rooms were covered in wood paneling, freshly painted with an electric maroon color. The paneling looked like it was laminated over the original walls, as there were no electrical outlets or phone jacks visible. The walls were clean and bare, the color of theatre curtains. It all harkened back to the Vietnamese Liberation Army moving in and closing the show.

Not far away was the War Remnants Museum, which is hugely popular with foreign tourists looking over the American military equipment and photographs of atrocities and napalm and Agent Orange victims and watching films of the same. The building is a Brutalist block, also from the '60s, with an open ground floor. It was originally built for use by the American Information Agency. The upper floors, apparently windowless, are half-covered with decorative marble plate, and there are stains beneath where they abruptly stop. The other half of the face of the building is raw concrete, emblazoned with the round insignia of the museum, a white dove superimposed over falling bombs. The facade seems to symbolize uncovering, as if this present museum provides information that the building's original inhabitants were at pains to deny. I was also told that the Vietnamese builders stopped the job halfway and stuck the insignia on to be done with it. That too, is very Vietnamese, as I am beginning to understand it: metaphor or symbolism arriving through inadvertence.

Not far away was the War Remnants Museum, which is hugely popular with foreign tourists looking over the American military equipment and photographs of atrocities and napalm and Agent Orange victims and watching films of the same. The building is a Brutalist block, also from the '60s, with an open ground floor. It was originally built for use by the American Information Agency. The upper floors, apparently windowless, are half-covered with decorative marble plate, and there are stains beneath where they abruptly stop. The other half of the face of the building is raw concrete, emblazoned with the round insignia of the museum, a white dove superimposed over falling bombs. The facade seems to symbolize uncovering, as if this present museum provides information that the building's original inhabitants were at pains to deny. I was also told that the Vietnamese builders stopped the job halfway and stuck the insignia on to be done with it. That too, is very Vietnamese, as I am beginning to understand it: metaphor or symbolism arriving through inadvertence.

November 19. Two days on Phu Cuoc Island in the Gulf of Thailand. Vietnam shares it with Cambodia, which has a military base on the northern tip. Arrival on double-prop plane from Saigon. Beautiful sand beaches, drowsy waves, friendly people, etc. Expansion is on its way and an international airport will open in 2010. After watching An Inconvenient Truth, I am not sure that hotels on low-lying islands are the most secure investments.

Receiving a massage on the beach brings the distinct advantage—if that is what one is looking for—of not having to explain that that is what one wants. The previous sessions—indoors, in the city, even in places that are listed as "legitimate"—seemed to be about negotiations for "extras." One young woman kept trying to jumpstart me with little pinches and hot breaths at odd moments, but I just don't seem interested, there is too much history surrounding this situation for me, too much predation. She turned out to be the best masseuse I've had, oddly enough. The Cham sites have their collections of stone phalluses and I have convinced myself that it is an integral part of the culture and might be an illuminating experience; but it is a threshold that I seem unable to cross.

My room in Phu Cuoc is from the Early Island Resort Period, rapidly becoming extinct. A stone foundation wall about two feet high, then wallboard and a peaked roof made from dried and woven palm fronds. Cold water, window openings without glass or screening, only a decorative wooden open grill across the center and large bed with mosquito netting. Two ugly Naugahyde chairs and a glass table and an open rack made of rattan. It is kept very clean, so what could be a depressing room is actually quite cheery.

November 18. I came to the area to see more of the art of the Cham dynasty, influenced by Khmer and other Hindu cultures that extended down through Java. Early one morning we visited the Cham ruins outside of Hoi An, in My Son. The Vietcong had hidden there during the siege of Hue and the American bombers so completely destroyed them, there wasn't much left. Later we visited the Cham museum in Danang, a place we both agreed is one of the best small museums anywhere. I give it the Walter Hopps Award for Most Thoroughly Considered Placement of Objects. The museum was built in the early part of the 20th century by the French and has the fairly standard semi-ornate Colonial style that is found everywhere. Every sculptural fragment is situated into its space like it belongs there. The museum concentrates on sandstone Cham sculptures found locally. The work dates from the 7th to 15th century. Every single object is beautiful, but in an earthy, elegant way that has no element of mystification. An exception is a very early statue of a slim Uma, with more patterned carving over its lower torso and legs than most of the other works. I have never seen it reproduced anywhere; it took my breath away.

Schoolchildren in crisp shirts lined the roadways to the Danang airport. As we got closer, soldiers indicated that we had to leave the taxi and walk. There were hundreds of young girls, wearing the traditional ao doi, cr¸me silk pants and a pale violet shell, holding paper Vietnamese flags of red with yellow markings. The President of China was arriving in Danang. We checked in to departures and had a perfect view of his arrival. The airstrip had a backdrop of dramatic mountains in heavy clouds and the President got off the plane as the sun began to set. All the girls screamed as if he were a Beatle.

November 17. The Lonely Planet guide once again disappointed when it described Hoi An as a place to linger a few extra days. My trust in it is slowly dying. I was once in the middle of Turkey and my LP had mentioned "the most pleasant town in Turkey." I took a bus there. It took 24 hours. The town, Amasya, was worth the trouble. Hoi An is another matter. I couldn't wait to leave this tourist-heavy seaside town. Its "charming" old architecture is over-stuffed with souvenir shops. There is the constant pressure of hawkers for postcards, fruit, water, motorbike rentals, hotels, guides, newspaper or shoeshine, everyone yelling "Hello! Hello! Where are you going?" New hotels cater to tour groups with bargain prices for rooms with pool use and breakfast included. They're all done in a weird Chinese-Transylvanian dˇcor. There are enormous amounts of mass-produced paintings, furniture, objects; even the marble sculptures in the parks come under the category of visual Muzak. What was once called kitsch is now a large part of Vietnamese culture.

November 11. Waking to the under-growl of the motorbikes brings a sense of dread. I think of Philip Larkin when he said he would visit China if he could come back the same day. I always forget until it's too late that I am an unenthusiastic traveler. By then I am on a plane or stuck in the wrong hotel or lonely. Hearing the city below means another day of taking on the unfamiliar. There never seem to be passive moments: such is the need for psychic adjustments. Then out of nowhere serenity arrives for a while. Traveling does seem to produce a personal narrative even if it's artificial and drawn from a known text. A piece published in two parts in Artforum in the mid-'80s by Carter Ratcliff, titled "Bagpipes on the Shore," distinguished how the traveler differs from the tourist. It was prompted by the art critic and poet's reaction to a lot of the "What am I doing here?" writing that attempted to find the marvelous in the resolutely unpicturesque: the writer as topographer.

I've met people that travel because they have read Bruce Chatwin or Paul Theroux. I have also seen people clambering over the old stones in Angkor Wat or in Tikal dressed like Indiana Jones. I cringed, in those moments, at what was perhaps an unacknowledged inner identification. I once saw Paul Theroux in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Ho Chi Minh City. I halted at the sight of him and exclaimed his name. He denied he was who he was. I don't know one woman that likes to read Theroux.

I've met people that travel because they have read Bruce Chatwin or Paul Theroux. I have also seen people clambering over the old stones in Angkor Wat or in Tikal dressed like Indiana Jones. I cringed, in those moments, at what was perhaps an unacknowledged inner identification. I once saw Paul Theroux in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Ho Chi Minh City. I halted at the sight of him and exclaimed his name. He denied he was who he was. I don't know one woman that likes to read Theroux.

I got interested in moving around when I began reading V.S. Naipaul, Theroux's reluctant mentor. I remember being thrilled by finding myself in a miserable hotel in Sumatra. I felt I'd entered one of his stories. An even earlier stimulus was seeing Hayley Mills in The Moonspinners, a movie from my childhood that demands the phrase "best forgotten," but taught me it's possible to go to different places. I still remember that opening scene where she was on a beat up old bus full of animals and peasants heading up a hill on a Greek island. Graham Greene defined the Romantic poets as "sensing God in the most barren regions, as if He were a poet of escape whom it was necessary to watch tactfully through spyglasses."

Another definition of the Romantic is one who would rather journey hopefully than arrive. I do not know exactly why I am here; I have given myself things to do, but they don't take up all of the six months allotted by the grant. The rest comes under the heading of getting to know the two countries I have been chosen to research.

The most interesting travel writer right now is the very literary Geoff Dyer. His Algerian journal has an entry from Camus: There is no pleasure in traveling. It is more an occasion for spiritual testing. If we understand by culture the exercise of our most intimate sense—that of eternity—then we travel for culture.

I wanted to go to central Vietnam to visit Hue, but for unclear reasons. I thought it was a more ancient place; it was, in fact, the Royal seat in the 1800s, a time not so eternal, when autonomy briefly flourished before the arrival of the French. Soon after, the Nguyen succession, whom many streets, plazas and products are named after, became figureheads. Hue may be remembered as the place where some of the heaviest fighting took place during the Tet, 1968. The Vietcong came and took over the city as they simultaneously made 100 other offensives, including a takeover of the American Embassy in Saigon. In the takeover of Hue, the Vietcong did what the Khmer Rouge later performed on bigger scale: they murdered the bureaucratic, religious and intellectual classes of the city.

Hue was a sweet, friendly town. Its citadel and the remains of the royal city were on the far side of the Perfume River (what a name) from the tourist area. We rented bicycles and then went through the standard routine of stopping at corners to have the local bicycle repairperson inflate the tires and tighten the breaks. Then after another kilometer or so, the next roadside repairman oiled the chain and cluster. By then the 75 cent rental cost about $2.25.

Hue accommodated bicycles well; there were few cars, the streets were wide and the area was just hilly enough to be interesting. The city seemed to attract cultural tourists, so there were less beach-oriented or "Survivor"-like, adrenaline addict visitors to contend with. We planned a loop through an area of Royal Tombs, and within a few minutes, we left the storefronts behind and were in open country. A large pine forest on a hill appeared to the right, and then fields and hills surrounded us. An old gate with a few motorbikes parked in front slowed us down and we walked through it to a covered pavilion. There was no one sitting at the formal cloth-covered tables and chairs, and terrible, Yanni-like music played too loud. It seems to be everywhere and is the scourge of the nation, but as someone once told me, "Hey, man, it's their country."

This left us in a verdant, shaded, and silent antique restaurant. It had the best Vietnamese food I'd ever eaten. The lunch defined a familiar dish that is available in New York. On one plate came long thin strips of pork with wide bands of fat at the top and bottom. There were cloves of garlic on another and a stack of rice wrappers, imported from a northern province. There were pickled vegetables and a large pile of aromatic leaves, mint, scallion, basil and a dozen others. You're supposed to make sure you have one sprig of each of the fifteen different leaves when you combine them with the other ingredients in the wrapper. Then you dip it in the funky, peppery sauce. After that was red pepper-dusted fish cooked in a clay pot, a soup with morning glory leaves (very popular here), cr¸me-caramel and coffee.

The tomb of the Emperor Khai Dinh is set on a steep hillside and has 35 steps to the top. It's from the 1920s. Hokum reigned with faux marble walls and a side room with blown-up black and white photographs of the Emperor in ornate gilt frames. Odd images such as bat motifs with spread wings adorn exterior columns. One lovely touch by a groundskeeper was a bare sapling laid across a stairway where cement was drying.

Furthest from town was the tomb of Minh Mang that's not architecturally significant but distributed on a beautiful serene site. The emphasis is on harmony with nature. I continue to be struck by how the value of harmony in art is as remote from this time as some distant galaxy. It seems to have died in the early 19th century.

Heading back from the tombs, we bicycled past a roadside market. Haunches of hog lay on tables in the sun, attracting flies. Further on, we passed the swept grounds of local temples and went along the Perfume River just before dusk, at the time I call the "burning hour," when everyone lights their fires. I love pedaling through Southeast Asia in the country at dusk. It's when the world seems most full of sociability. Kids on bikes slow down next to you and try out their English. To be enmeshed in the movement and commerce of semi-rural society can be a wonderful thing.

November 8-10. With the arrival of my colleague, the artist Mary Weatherford, there entered a period of less introspection. We scheduled three days of kayaking in Halong Bay accompanied by two nights in the base camp, and I ended the period in the Victoria II Hotel in Hanoi. The hotel is near Hoan Kiem Lake, but on the other side of the Tourist section. It's a narrow hotel, only two rooms per floor. The many high, narrow buildings in Vietnam are the result of high property taxes on frontage. Mr. Sinh, one of the managers, was sometimes in the bag in the middle of the afternoon. He always jumped up and called me "Sir," no matter how drunk he was. I loaned him money twice; he paid it back and then offered me a loan as a return favor. Everyone was always very nice. They seemed like a typical bunch of local guys, but it made a difference that Tran Luong set me up there. They appeared impressed with him.

There is a grade school across the street from the hotel with a large band. At least twice a week, usually on weekends early in the morning, a hundred little kids march down the street, beating in unison on snare drums. Some speakers are around the area. The last time I was in Hanoi, there was a speaker in a tree outside my window that spewed Vietnamese announcements every morning. Now, at this school, there is a recording of a carillon several times a day, and a ringing of a gong-like bell at six and twelve, like the siren that went off every day at noon on Staten Island. One of Proust's servants on hearing the Angelus at Combray: "It's only a poor old bell but you think, 'My brother's on his way back from the fields now.'"

There is a grade school across the street from the hotel with a large band. At least twice a week, usually on weekends early in the morning, a hundred little kids march down the street, beating in unison on snare drums. Some speakers are around the area. The last time I was in Hanoi, there was a speaker in a tree outside my window that spewed Vietnamese announcements every morning. Now, at this school, there is a recording of a carillon several times a day, and a ringing of a gong-like bell at six and twelve, like the siren that went off every day at noon on Staten Island. One of Proust's servants on hearing the Angelus at Combray: "It's only a poor old bell but you think, 'My brother's on his way back from the fields now.'"

My last time in Hanoi, I also attempted to go to Halong Bay. Some of the major attractions, such as this one, a World Heritage site, are difficult to get to unless you book some kind of tour. I did one from my very questionable hotel (I noticed it has gone out of business). A large roomy bus showed up in the morning and I got on and got comfortable and a few minutes later, we were transferred to a minivan that had a dozen people in it. The tour guide in the front seat yelled a lot of happy talk, asked our names, and then played loud Beatles recordings as we headed down the highway to Haiphong harbor, two and a half hours away. I came to the conclusion after an hour had that I couldn't do this. They let me out on the highway, at my insistence, and told me I couldn't get a refund. In all fairness, the guide was most gentle and considerate and asked me why I wanted to abandon the trip. I just said I thought it wasn't for me.

This time I did some research on the best Halong Bay trip. There are many: cruise around on a Chinese junk, overnight on a sailboat (I heard rumors of rats on the sailboats, and I never did see any in the bay), one night in a hotel on Cat Ba Island, two and three days kayaking. Mary, who is from California, wanted to do the kayaking trip, which was the most expensive: three days kayaking, two nights in a base camp for $188 per person. It turned out to be a good choice. A large roomy bus to the harbor, a considerate guide and no piped in music at any point.

The time on the bay was quiet because kayaks don't have engines. Occasionally, a day-tripper boat would pass, spewing diesel smoke from the loud putt-putt engine as half a dozen miserable looking tourists peered out.

Halong Bay takes up an awesome amount of area. We thought we kayaked great distances, but when we were shown where we had gone on the map, we discovered that it was about one percent of the total area, if not less. It can easily be called Vietnam's Grand Canyon, but unlike that place, it is most appropriately about negotiating water. The large masses of rock are close to uninhabitable. There are terns, cranes, and egrets, black kites flying and nesting among the large upturned sandstone cliffs, and some monkeys, too. The human population is made up of net and traps fishermen (and women) that live in small houses beneath the sheer masses of rock. The aqua blue and green shacks seem to float on water level, temporarily secured upon piles, like docks. There are many parts of the bay where none of these permanent residents live.

The experience fell just short of exhilarating because of the water quality, which was less than pristine. When I asked our guide Son about what happens during the monsoons, he said that the bay authority comes around with storm warnings, so the fishing population may commence towing their houses to safe harbors.

November 7. The Vietnam News, the English language daily paper, ran an article on my exhibition. Most of it was taken verbatim from my artist statement, and what they did change was just enough to skew the meaning. In addition, the anonymous writer added, falsely, that I made the paintings from rags I picked up from the streets of Hanoi. The headline reads, American Artist Puts Hanoi Down On Canvas. I didn't know about the feature until a friend gave me a copy as I was on my way to an event at the Goethe Institute. A German DJ, in town to collaborate with local electronic composers, played some kind of House music as part of an introductory evening. I am old enough now to be uninterested in DJs; more accurately, the thought of them bores me. Some of the music had words, so it was not strictly techno, I was told. I have no idea what any of this stuff is. I went up to the balcony and viewed the younger segment of the very attractive and very small Hanoi art world dancing below, at the front of the crowd. The headline reads, American Artist Puts Hanoi Down On Canvas. I didn't know about the feature until a friend gave me a copy as I was on my way to an event at the Goethe Institute. A German DJ, in town to collaborate with local electronic composers, played some kind of House music as part of an introductory evening. I am old enough now to be uninterested in DJs; more accurately, the thought of them bores me. Some of the music had words, so it was not strictly techno, I was told. I have no idea what any of this stuff is. I went up to the balcony and viewed the younger segment of the very attractive and very small Hanoi art world dancing below, at the front of the crowd.

It felt good to be up on the balcony instead of wondering why I wasn't down there. A few of the older Hanoi painters, with their long white hair and beards, were watching with me. I met them at my opening and enjoyed saying hello again. Then I went downstairs, and with the music blaring, the most convenient response to "How are you?" was to pull the article from my back pocket. I was showing it to Duong, a young Hanoi artist, when a French ex-pat Saigon artist with a ponytail came over. He looked at it and covered part of the headline so it read American Artist Puts Hanoi Down.

November 4-5, 2006. After sleep, Thu brings me to a local place right in the center of the tourist section where I never venture except to buy DVDs. (I bought two Ozus the other night.) I got a very soothing plate of chicken threads over sticky rice and a glass of green tea and went back to bed. I then finished Duong Thu Huong's No Man's Land, her fourth and most recent novel that I had begun after I finished my plane reading, Patricia Highsmith's This Sweet Sickness. From No Man's Land, what may or not be an insightful description of this country:

"No, they have real talents. First, because they have the experience. The Chinese have been involved with commerce since antiquity. They knew even back then how to build boats that crossed the seas, they knew the value of money-while the rest of us, we Vietnamese, were praising the virtues of honest poverty and the purity of the soul and were disdaining those who made a fortune through commerce and not through farming or by working as some imperial bureaucrat. We made bad choices from the beginning, so we're paying the price."

A lecture on my work at the Nhasan studio, a stilt house that was the site of the first alternative installations and performances by Vietnamese artists-a good-size crowd, maybe twenty-five Vietnamese artists and friends, Tran Luong translating. After the first half hour or so, it appears that this audience is seeing how my abstract paintings have been influenced by the environment of Vietnam. I bring up Baudelaire and the Painter of Modern Life, how the French poet said the artist has to be immersed in the modern world. I told them about how I thought this ancient, rural culture bringing itself into the present was the important modern experience in this historical moment. So I laid it out there for myself as well as for the audience and I felt like I was heard and understood, and it was very satisfying.

A friend arrives and we take our bicycles out over the Long Bien bridge, built by the same company that built the Eiffel Tower. It is a railroad bridge that allows only motorbikes and bicycles and pedestrians. It was the chief target of American bombers during the war. About halfway over the approximately three-quarter-mile span, we stopped and I pointed out the subsistence fishing families' shacks in the river below, saying to my friend, "Well, there's the chief influence on my work down there."

November 3, 2006. I am not feeling very well: Tired, stomach problems, pains high in the chest. I have the opening of my exhibition tonight, and I am nervous about it. Minh Phuoc, who runs the gallery, asked for a title, and I told him I wanted Homage to Hanoi. I had written an artist's statement, which my friend the artist Thu Vu later translated into Vietnamese, that described how I liked the way the city of Hanoi addresses the senses, how a lot of the local architecture is improvisational, how nature is continually present, how I hoped that St. Joseph's Cathedral is never painted. The title referred to all the artists in Hanoi I knew, and it was also an homage to Tran Trung Tin, who, to me, is the great Hanoi abstract painter. (See: http://artcritical.com/fyfe/JFHanoi.htm)

I was feeling a little woozy and stressed on my way to the gallery. It has an open front, so you just roll up the gate and there it is. I had known the space because I reviewed a performance there a few years ago. The paintings were relatively small, and I liked how they worked proportionally with the divisions in the room and the height. Franz Xavier Augustin from the Goethe Institute rolled in on his motorbike and dropped a bunch of announcements for what would be opening at the center two days later. He said, "So you're having a show? That's fine." Several older well-dressed Vietnamese gentlemen arrived in a taxi, with a woman in an evening gown, and they said some congratulatory words to me in French. Younger Vietnamese artists arrived, some of the expats, Natasha from the gallery, many familiar faces. Phuoc had to guide me into the crowd at one point: I was not really trying to do the shy thing, I just wasn't feeling that well. Too much indiscriminate eating probably gave me a slight viral infection. It happens every time I come here and I always forget that it does.

November 1, 2006. Karen Gottschang Turner and Phan Thanh Hao held a discussion about the women volunteers in the Liberation Army of Vietnam. Their book, Even the Women Must Fight Memories of War from North Vietnam, is an incomplete history of about 200,000 women who left home in order to maintain the Ho Chi Minh Trail. A lot of them came down with malaria, gave up their brief marriageable years, or died. Apparently, Uncle Ho worried about them enough that he sent psychiatrists to see how they could stand up under brutal conditions, working in the jungle and under bombardment for years at a stretch. One particular image: As the army caravans came through under the cloak of darkness, the women would stand in the shallow areas of the rivers the convoys were crossing, naked from the waist up, their skin reflecting the moonlight to help guide the caravans' crossing.

Bicycle ride out to the Museum of Ethnology: seven kilometers on a winding road past the very large West Lake, a back-and-forth breeze on a relatively dry, clear day. Buses, motorbikes, bicycles, and now more and more cars and SUVs with drivers who lean on their horns like they own the road. Passing private residences along the lake, walled; schoolyards with the kids in their starched whites, lots of small stands next to the road, people selling vegetables and fruit; further on, engine repairs, stands for bottled water and candy, a kid crossing with a good-size roast dog on a woven tray, almost doubled over from the weight, a market for clothes, and food in a temple and on the surrounding grounds. Dust kept blowing in my eyes, horns kept blaring, one of the many moments when I didn't know what I was doing, but I thought that this was the most common experience you can have on this earth. This is the modern world, being rushed along a dirty road that is a market, still as ancient as it is new. I had bought a one-dollar DVD of Diary of a Country Priest the night before, and I was having an argument with myself. How could Bresson be a spiritual filmmaker when Godard was the one who always had the muscular interruption of traffic in his films?

On the plane on the way over I finally saw An Inconvenient Truth. As I watched it I looked out the window and saw the brown burned jet fuel come out of the engine. If I looked down I could see arctic wastes with big cracks running through pristine white landscape. (True.)

The most important objects at the ethnological museum were the pieces of hand-carved furniture in the communal longhouses of the Ede ethnic minority. There was a very, very long flat bench that must have been from the center of a tall tree, but there were also several tables with flat, wide legs that curled out from underneath, narrowing as they reached the floor. This and the very small stools, cut in several variations, seemed very basic, modern, and aesthetic. The degree of abstraction in relation to function, as well as the material itself, a very tough wood that was almost like iron, was very impressive. A little like the Pierre Jeanneret furniture that was designed for Chandigarh, India. An aesthetic experience, married to more wondering about how my show will be received.

I saw a documentary last night about a 95-year-old French Communist who would not participate in the film. His Viet Kieu daughter, her mother, and his wife were major presences. The mother was quite beautiful, a white-haired Vietnamese woman who spoke French. The Silence of the Rice Fields had a lot of interviews with other old French communists who hid in the jungle and advised Uncle Ho and the Vietminh after the fall of Dien Bien Phu. Some of them just died and not much could be done about it. They were a big secret. One interview was with a Vietnamese artist, a very old, irascible chain smoker, who designed the first paper money for the North Vietnamese government after the partition. It was printed on rice paper with Chinese ink. He was very funny, talking about how they would have exhibitions in the jungle, but not many people came, "...because it was the jungle. We would send the word around and some people would come at night with flashlights and we would stick the drawings on the trees." He also didn't see why Americans had wars, because everyone ends up wanting to be an American anyway.

return

to blog index

|

|

Not far away was the War Remnants Museum, which is hugely popular with foreign tourists looking over the American military equipment and photographs of atrocities and napalm and Agent Orange victims and watching films of the same. The building is a Brutalist block, also from the '60s, with an open ground floor. It was originally built for use by the American Information Agency. The upper floors, apparently windowless, are half-covered with decorative marble plate, and there are stains beneath where they abruptly stop. The other half of the face of the building is raw concrete, emblazoned with the round insignia of the museum, a white dove superimposed over falling bombs. The facade seems to symbolize uncovering, as if this present museum provides information that the building's original inhabitants were at pains to deny. I was also told that the Vietnamese builders stopped the job halfway and stuck the insignia on to be done with it. That too, is very Vietnamese, as I am beginning to understand it: metaphor or symbolism arriving through inadvertence.

Not far away was the War Remnants Museum, which is hugely popular with foreign tourists looking over the American military equipment and photographs of atrocities and napalm and Agent Orange victims and watching films of the same. The building is a Brutalist block, also from the '60s, with an open ground floor. It was originally built for use by the American Information Agency. The upper floors, apparently windowless, are half-covered with decorative marble plate, and there are stains beneath where they abruptly stop. The other half of the face of the building is raw concrete, emblazoned with the round insignia of the museum, a white dove superimposed over falling bombs. The facade seems to symbolize uncovering, as if this present museum provides information that the building's original inhabitants were at pains to deny. I was also told that the Vietnamese builders stopped the job halfway and stuck the insignia on to be done with it. That too, is very Vietnamese, as I am beginning to understand it: metaphor or symbolism arriving through inadvertence.

I've met people that travel because they have read Bruce Chatwin or Paul Theroux. I have also seen people clambering over the old stones in Angkor Wat or in Tikal dressed like Indiana Jones. I cringed, in those moments, at what was perhaps an unacknowledged inner identification. I once saw Paul Theroux in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Ho Chi Minh City. I halted at the sight of him and exclaimed his name. He denied he was who he was. I don't know one woman that likes to read Theroux.

I've met people that travel because they have read Bruce Chatwin or Paul Theroux. I have also seen people clambering over the old stones in Angkor Wat or in Tikal dressed like Indiana Jones. I cringed, in those moments, at what was perhaps an unacknowledged inner identification. I once saw Paul Theroux in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Ho Chi Minh City. I halted at the sight of him and exclaimed his name. He denied he was who he was. I don't know one woman that likes to read Theroux.

There is a grade school across the street from the hotel with a large band. At least twice a week, usually on weekends early in the morning, a hundred little kids march down the street, beating in unison on snare drums. Some speakers are around the area. The last time I was in Hanoi, there was a speaker in a tree outside my window that spewed Vietnamese announcements every morning. Now, at this school, there is a recording of a carillon several times a day, and a ringing of a gong-like bell at six and twelve, like the siren that went off every day at noon on Staten Island. One of Proust's servants on hearing the Angelus at Combray: "It's only a poor old bell but you think, 'My brother's on his way back from the fields now.'"

There is a grade school across the street from the hotel with a large band. At least twice a week, usually on weekends early in the morning, a hundred little kids march down the street, beating in unison on snare drums. Some speakers are around the area. The last time I was in Hanoi, there was a speaker in a tree outside my window that spewed Vietnamese announcements every morning. Now, at this school, there is a recording of a carillon several times a day, and a ringing of a gong-like bell at six and twelve, like the siren that went off every day at noon on Staten Island. One of Proust's servants on hearing the Angelus at Combray: "It's only a poor old bell but you think, 'My brother's on his way back from the fields now.'"

The headline reads, American Artist Puts Hanoi Down On Canvas. I didn't know about the feature until a friend gave me a copy as I was on my way to an event at the Goethe Institute. A German DJ, in town to collaborate with local electronic composers, played some kind of House music as part of an introductory evening. I am old enough now to be uninterested in DJs; more accurately, the thought of them bores me. Some of the music had words, so it was not strictly techno, I was told. I have no idea what any of this stuff is. I went up to the balcony and viewed the younger segment of the very attractive and very small Hanoi art world dancing below, at the front of the crowd.

The headline reads, American Artist Puts Hanoi Down On Canvas. I didn't know about the feature until a friend gave me a copy as I was on my way to an event at the Goethe Institute. A German DJ, in town to collaborate with local electronic composers, played some kind of House music as part of an introductory evening. I am old enough now to be uninterested in DJs; more accurately, the thought of them bores me. Some of the music had words, so it was not strictly techno, I was told. I have no idea what any of this stuff is. I went up to the balcony and viewed the younger segment of the very attractive and very small Hanoi art world dancing below, at the front of the crowd.